|

Abraham Lincoln’s

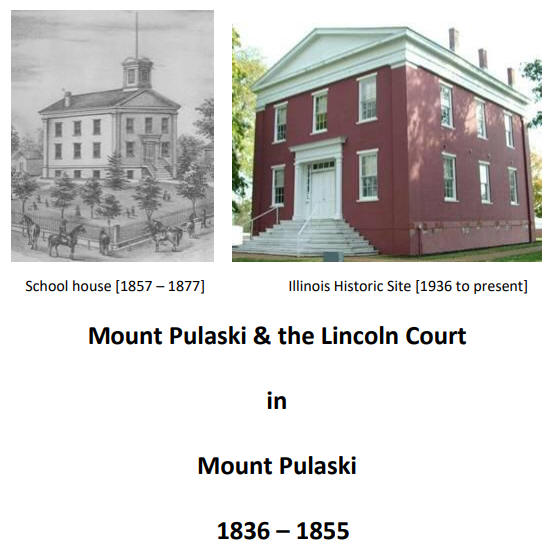

Connection In the mid-1800’s, covering the Illinois 8th Judicial Circuit required traveling approximately 450 miles by horseback and horse and buggy through fourteen counties, including Mount Pulaski, the Logan County Seat from 1848 to 1855. However, it was not until 1849 that Mr. Lincoln re-joined this Judicial Circuit, having served two years in the United States House of Representatives: 1847 - 1848. Mr. Lincoln immensely enjoyed his days traveling on the judicial circuit, meeting and talking with many people, friends, and other lawyers. He delighted in listening and telling stories along the way. Mr. Lincoln “allowed” Judge David Davis and the other lawyers to stay at the Mount Pulaski House Hotel, while he resided with friends that he had made, namely the Capps, Lushbaugh and Beidler families of Mount Pulaski. Elizabeth Lushbaugh Capps, daughter of Thomas P. Lushbaugh, related many years later that Mr. Lincoln enjoyed staying in more comfortable and more private surroundings such as her parent’s home. She goes on to write that Mr. Lincoln “sat at the table in our home, talking in a lively manner with his hair all ruffled up, as it usually was in those days, for he had the habit of running his fingers through it occasionally when talking.” Samuel Linn Beidler became a close friend of Mr. Lincoln’s and was the only one to meet him in Lincoln at the train station on Oct. 15, 1858. Mr. Lincoln had quietly arrived in Lincoln the day before his speech. Stephen A. Douglas was currently in town giving a speech. Beidler accompanied Mr. Lincoln to the local hotel that day. The next day, over 50 horse-pulled wagons jammed with admirers and others on horseback and in buggies from Mt. Pulaski arrived in Lincoln to hear ol’ Abe speak. A large sign, “Mt. Pulaski supports old Abe” could be prominently seen over the crowd of 5,000 people. A few years before, Mr. Lincoln had purchased the newspaper, Gazette, in Springfield, which was a German-written newspaper that he had delivered to Mt. Pulaski and other parts of central Illinois that had heavy German populations. Mr. Lincoln and his law partner, William Herndon, participated in three notable trials. Two were the Cast-Iron Tombstone Trials, one held in Mount Pulaski in 1854 and the other held in the county seat of the newly founded town of nearby Lincoln in the fall of 1855. The plaintiffs in these two trials – William E. Young and Nathaniel Whitaker, both of Mt. Pulaski – claimed that they should have their money and property returned to them since the manufacturing patent rights to the Cast-Iron Tombstones did not include the actual tombstones, but merely the decorative part of the tombstones. Similarly, the plaintiffs in the 1853 Horological Cradle trial - John & George Meyer and McCarty Hildreth, all of Mount Pulaski, claimed that the manufacture of the clock-spring driven cradles was not covered by the patent rights they had purchased – that these rights merely covered the ornamental designs of the cradles. Mr. Lincoln served as defense attorney in all three of these trials. Indeed, these cases fitted in with Mr. Lincoln’s fascination with mechanical and manufacturing processes. Yet, Mr. Lincoln’s profound belief that a man’s signature was his final word led him, perhaps, to under-estimate each plantiff’s personal impact and sorrowful appeal on the minds of the jury. He lost all three cases. Subsequently, he and Herndon appealed these cases to the Illinois State Supreme Court. It was not until Mr. Lincoln’s Presidency years that these appeals were finally resolved. Herndon notified President Lincoln in 1864 - during the midst of his tribulations with the devastating Great War between the states - that they had lost all three appeals. This notification letter from Herndon has been documented, but it is not certain that President Lincoln had the time to read and reflect on it. While Judge David Davis was instrumental in getting his friend, “Honest Abe” Lincoln nominated and eventually elected to the United States Presidency, the newly-elected President did not offer Davis a position in his new administration [as we know now, Lincoln wanted a more-experienced "Team of Rivals"]. Later, in 1862, Judge David Davis did accept President Lincoln’s offer to become an associate justice of the United States Supreme Court. Mount Pulaskians - friends, acquaintances, county clerks, mercantile men, and lawyers - could proudly state that they had much to do with the foundation of the 16th President of the United States, whom many think is the finest and most famous of all of our American Presidents. & development of Mount Pulaski <-- click here

|

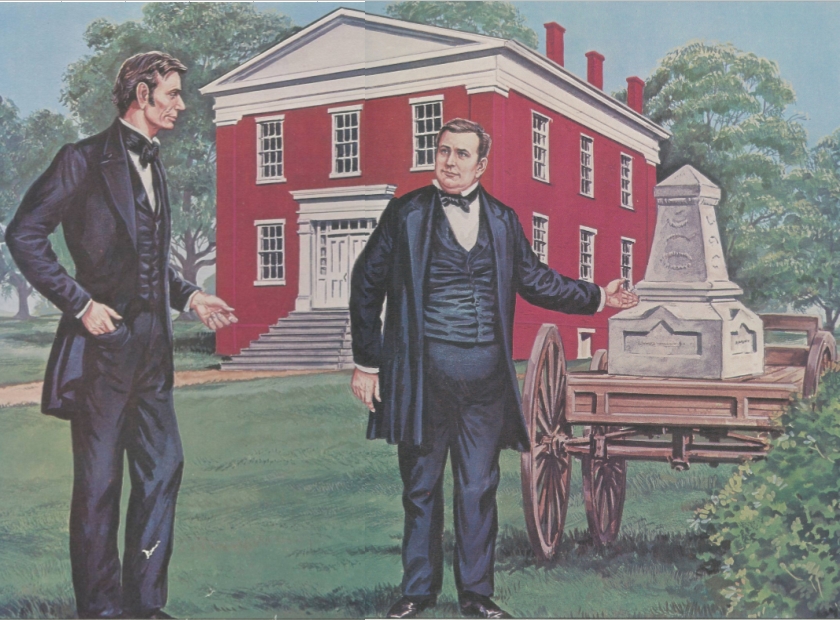

. Mr. Lincoln & Judge Davis reflecting on a cast-iron tombstone <-- click here Cast-Iron Tombstone Trials 1854) Mt. Pulaski Courthouse 1857) Lincoln IL Courthouse Young v. Miller. Flinchbaugh had a patent on a cast iron cemetery monument. Miller, as an agent for Flinchbaugh, sold exclusive rights in the patent for most of the counties in Illinois to Whitaker in exchange for eighty acres of land and $1,000, and sold the patent rights for Michigan to Young in exchange for 160 acres of land. Believing that Miller had defrauded him, Young sued Miller to rescind the contract and to recover the land. Whitaker separately sued Miller to rescind the contract and to recover the land he had given Miller (Miller & Flinchbaugh v. Whitaker). Young charged that the contract was void because the patent was only for the ornamental design, that the monument was well known in Europe and the United States, and that the patent was frivolous and of no benefit to society. The court ruled for Miller, and Young appealed to the Illinois Supreme Court, which considered Whitaker's and Young's cases together. The supreme court reversed and remanded the judgment, ruling that Young should have added Flinchbaugh as a defendant. In the remanded case, the court ruled for Young, rescinded the contract, and ordered Miller to recover the lands. Miller and Flinchbaugh appealed to the Illinois Supreme Court, but the court dismissed the appeal because Miller and Flinchbaugh failed to assign errors. Miller and Flinchbaugh retained Herndon, and the Supreme Court reinstated the appeal. Young died, and Randolph, the administrator of Young's estate, replaced him in the case. The Supreme Court reversed and dismissed the judgment for Young. Justice Beckwith stated that Miller's representations of the monument were not fraudulent and that the sale of a patent right would not be set aside on the ground of misrepresentations as to the durability and probable sale of the patented articles, since such representations were matters of opinion. Whittaker v. Miller. Illinois Supreme Court manuscript: Cast-Iron Tombstone Case. Lincoln Presidential Library, Springfield, IL File ID: L00994 Jan. 1864. Flinchbaugh had a patent on a cast iron cemetery monument. Miller, as an agent for Flinchbaugh, sold exclusive rights in the patent for most of the counties in Illinois to Whitaker in exchange for eighty acres of land and $1,000, and sold the patent rights for Michigan to Young in exchange for 160 acres of land. Believing that Miller had defrauded him, Whitaker sued Miller to rescind the contract and to recover the land. Young separately sued Miller to rescind the contract and to recover the land he had given Miller (Miller & Flinchbaugh v. Randolph). Whitaker charged that the contract was void because the patent was only for the ornamental design, that the monument was well known in Europe and the United States, and that the patent was frivolous and of no benefit to society. Whitaker also claimed to have been so intoxicated that he did not know what he was doing when he made the contract with Miller. The court ruled for Whitaker. Miller retained Lincoln and Herndon and appealed to the Illinois Supreme Court, which considered Whitaker's and Young's cases together. The Supreme Court reversed and remanded the judgment, ruling that Whitaker should have added Flinchbaugh as a defendant. In the remanded case, the court again ruled for Whitaker, rescinded the contract, and ordered Miller to recover the lands. Miller and Flinchbaugh appealed to the Illinois Supreme Court, but the court dismissed the appeal because Miller and Flinchbaugh failed to assign errors. Miller and Flinchbaugh retained Herndon, and the Supreme Court reinstated the appeal. The Supreme Court affirmed the judgment for Whitaker after determining that there was no error in the circuit court record. Locals have searched the area for these “cast-iron” tombstones. Three have been located in the Mt. Pulaski Cemetery, one in the Lake Fork Turley Cemetery, one in the Bowers-Templeman Cemetery and one in the Chestnut “Randolph” Cemetery. Perhaps the results of the 1854 and 1857 tombstone trials had something to do with the discouragement of this new procedure in metallic tombstones. “Beginning in the 1870’s, inexpensive monuments in American cemeteries began to be made of zinc...Their cast-iron fountains with classicizing zinc statues were occasionally placed in cemeteries, originally painted light colors in imitation of stone. Corrosion is a potential problem for any metal monument, especially in highly polluted or seaside atmospheres …Nevertheless, white-bronze monuments, which were meant to remain unpainted, survive remarkably well. Perhaps this is because the cast metal was relatively pure (more than 99% zinc) and the joining metal was also composed of zinc.”  1850’s Illinois 8th Judicial Circuit by phil bertoni --> return to main page |